Secret Season: Falmouth

Colder, but not unwelcoming, what is it about the atmosphere of the coast in winter that draws us in? And why is maintaining our connection to nature year-round so important?

Summer is the peak of coastal activity: as temperatures drop, t-shirts are swapped out for woolly jumpers and the shore empties out. The sea turns an icier shade of blue, and as nature winds down around us, we often follow suit. But what do we miss if we miss out on time by the sea? And what draws us to the coastline in the colder months?

Image credit: Abbi Hughes

There’s beauty to be found in the cold, especially along rugged stretches of coast. A change in the seasons doesn’t have to keep us away. In fact, this darker, cooler atmosphere can be what draws us in.

Writer Wyl Menmuir’s book Draw of the Sea examined people’s relationship to the coast. For Wyl, winter is a time to appreciate the shifts in the landscape – nature is exposed and heightened. And by the sea, we’re at a boundary line: “Perhaps we can see nature at its rawest when we’re standing on the edge of the land, rather than in the middle of it. It taps into our desire to experience the sublime, which is something I’ve always been interested in.”

The sea might be turning colder, but the waves get bigger, and its colour becomes deeper, more complex. Weather patterns shift, affecting the way water moves, and all of this becomes so much more noticeable.

The sea during winter can put things in perspective, says Wyl. This comes with being at odds with nature at its most volatile – and that’s exciting, whether you’re right there in it, or watching from afar. “I can sit on the cliffs and watch surfers riding enormous waves in the autumn and winter swells, here in Cornwall on the north coast,” he explains. “And it’s those times where I see people riding really challenging waves, and, for me, the sea is just more interesting to watch when there’s a lot more movement in it.”

Against the high winds, dramatic cliffs and outcrops, this is where comfort is found. Wyl finds that the long views of the coast, the water, give a sense of perspective. Against the backdrop of something as expansive as the sea, our problems and fears feel smaller, more manageable.

Wyl compares that feeling, of standing on the cliff face, looking out at the water, to staring up at a dark sky full of stars. After confronting the enormity of nature, we feel more comfortable in our place within it. There’s a certain meditation to be found.

Image credit: Abbi Hughes

The wind, the skies, the sea, all have a profound effect on the mind and body. The human connection to nature is a powerful one – for many, it’s the key to surviving through tough times, a way to keep centred. Lizzi Larbalestier, of Going Coastal Blue – a blue health coach, spends time in blue spaces all year round, and encourages others to do so too, whether it’s actually getting into the water, or simply walking alongside it.

Movement, Lizzi says, is crucial for mental and physical health. “The coast encourages us to get outdoors, dressing for the weather to enable us to take in the fresh air and embrace the elements, creating a primal sense of nature connectedness that promotes stress reduction and improves sleep.”

As the coastline quietens down during winter, transforming into a more peaceful and quieter environment – it is a great place to pause and reflect on the year, with plenty of space to absorb the sweeping horizons, vast open skies, and glistening shoreline. “Spending time in blue space,” Lizzi says, “allows us to breathe well, to slow down, to think more clearly, to feel much more connected with ourselves, with each other and with the planet.”

With the approach of winter comes a desire to hunker down, sink into creature comforts, embracing warmth and light wherever we can find it. As Lizzi notes, getting natural daylight and spending time outdoors during this time of year is incredibly important for our wellbeing and that includes our physical and emotional health. But sunlight can be scarce mid-winter, so we should embrace and enjoy it where we can.

Spending time by water is great for our mental health. Water, in all seasons, in all forms, is inherently soothing. We are drawn to its feel, its colour and sounds. Lizzi explains that simply watching the waves can calm us down, creating “attention restoration with less complex and frenetic landscapes allowing our mind to drift into a more meditative state.”

“We breathe differently at the coast,” explains Lizzi, “positively impacting our heart rhythm, lowering blood pressure and enabling our nervous system to move into a parasympathetic state of rest and recovery.”

Image credit: Abbi Hughes

Lizzi depicts the sea as a “therapist or health practitioner, a partner for our lives to guide our intuition and keep us well”. “We gain a lot from a strong connection to the coast, but our relationship with all of nature is symbiotic.” she says. We can gain from it, but also need to give back.

“Take three for the sea,” recommends Lizzi. “Conduct a mini beach clean or get involved in a large community beach clean with the local community – these organised collective events not only help the ocean but being part of something purposeful in the form of community activism and advocacy can boost positive ‘feel good’ neuro chemicals like oxytocin and dopamine associated with what is known as the ‘helpers high’.”

From experiencing the sublime to feelings of perspective and breathing in the physical and mental benefits of being by the sea, there’s much to draw us to that unique beach atmosphere in the colder, quieter months.

This #SecretSeason, stay footsteps from the coastline: experience the beach atmosphere benefits.

Hushed beaches, misty cliffs, and the gentle sounds of the tide, this is Cornwall’s #SecretSeason – a moment for reflection, meditation, and creativity – a perfect time to visit Penwith’s artworld.

Penwith – Cornwall’s westernmost tip connected to the wild Atlantic, stretching all the way from Hayle around to St. Michael’s Mount – has long been celebrated for its rich artistic heritage. Its raw and rugged beauty is inspiration for both artists and art lovers. And from Marazion to St Ives, local artists and galleries recreate the winter landscape in softly coloured paintings and ceramics.

Cornwall’s #SecretSeason is a perfect time to discover its thriving art scene, so we visited some of this season’s exhibitions and hear from two local artists, Sarah Woods and Jack Doherty, on how winter shapes their creative processes and deepens their connection to the coastal landscape.

Begin your journey at Penzance, Cornwall’s major port town. In its quiet historic streets, you’ll find Penlee House Gallery & Museum home to an impressive collection of Newlyn School paintings. Upcoming in February 2025, The Shape of Things: Our place in a changing climate, will feature works of local artists who explore how Cornwall’s shifting land- and seascapes respond to environmental changes, inspiring hope and action for the future.

Image credit: Sarah Woods

Newlyn-based painter, Sarah Woods, paints her personal interpretation of the shifting atmosphere from her cozy studio. “Winter along the west coast has a timelessness – a feeling of the land and sea in harmony.”

With changing seasons, she witnesses the landscape quietly breathing and shifting as well. This way, her collections are unique to each season – her newest series captures this shifting landscape in autumn, drawing inspiration from “a palette rich in deep earthy tones, gathered from elemental movement of the ocean and a coastline warmed with autumnal light.”

As winter takes hold, the colours she mixes evolve again inspired by low-traveling light and dark ocean hues. The light “has a clarity that comes with the cold,” she says, slowing down the pace of things while the “landscape breathes.”

Image credit: Sarah Woods

In her studio, Sarah focuses on the process of painting rather than the outcome, describing it as “a continuous flow of time balanced between the coast at the studio.” Her practice is intuitive and tactile, shaped by an immediate response to the forms and colours she observes in the landscape. Whether focusing on large-scale canvases or intimate studies, she creates pieces that reflect nature’s rhythm, translating Cornwall’s wintery calmness into meditative works of art.

Building on Sarah’s introspective approach, the next stop on this artistic journey takes you to the small town of St Just. Here, The Jackson Foundation invites you into its industrial space where art and nature become one. The current exhibition showcases Kurt Jackson’s paintings, taking inspiration from Valency Valley in north Cornwall.

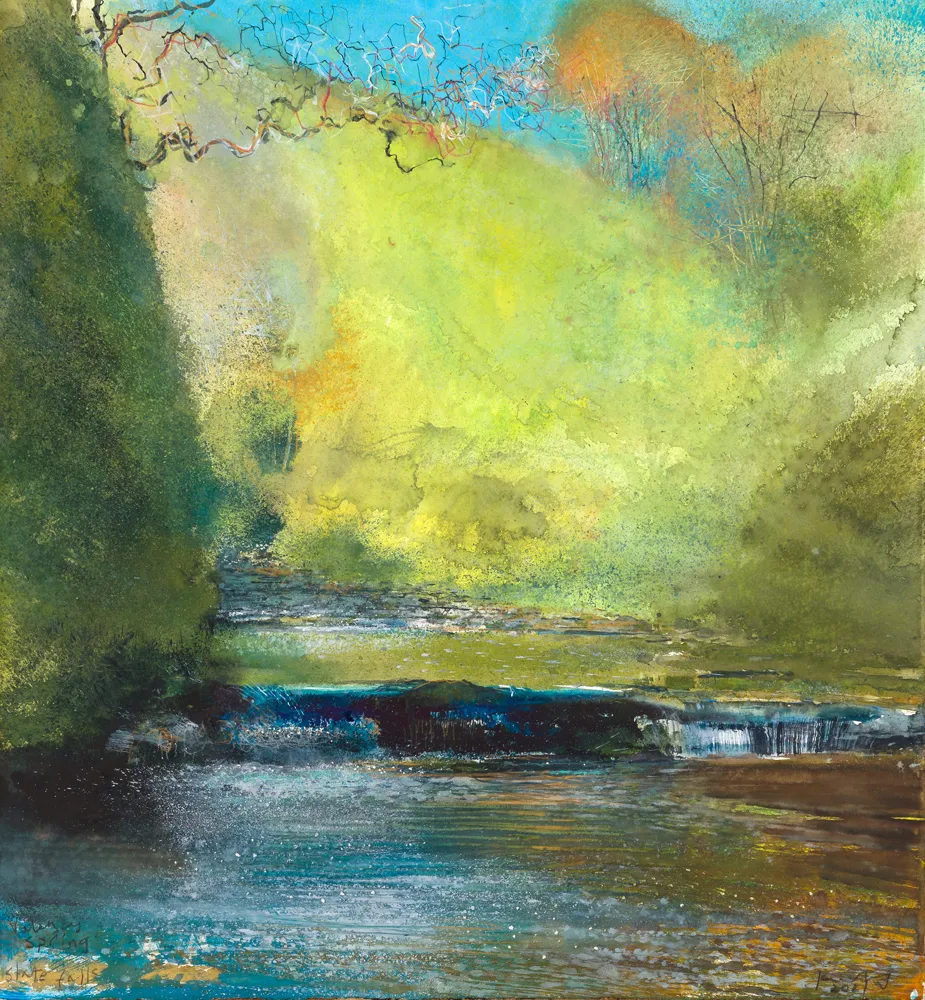

Image credit: Jackson Foundation Gallery

It features large-scale works capturing the valley’s wooded banks, flowing waters, and the Boscastle Harbour. The collection reflects Jackson’s philosophy that “no man ever steps in the same river twice” – each piece is a silent reflection on both a nostalgic past and a scenic future.

Image credit: Kurt Jackson

This play between nature’s physical environment and artistic response also unfolds in Jack Doherty’s ceramic work. In 2008, he became the first lead potter at Leach Pottery in St Ives, after it was refurbished, carrying forward its “modernist awareness of material and technique.” Today, Jack’s work is shaped by Cornwall’s jagged environment and changing weather. His recent exhibition, Weathering, reflects Cornwall’s shifting weather patterns and the passage of time that shapes not only the landscapes but also his ceramics.

Image credit: Jack Doherty

“The powerful combinations of colour in the grey, wet wind-blasted stones and moorland of West Penwith” inspire Jack’s minimalist approach. Using just one clay, one colouring mineral – copper, sourced from Cornwall’s mining history – Jack’s soda-fired porcelain creates a striking palette of greys, russets, and flashes of cerulean, all without glazes.

“The winter weather is an ever present influence on how we live here,” he says. Even when the dampness and wind challenge Jack’s drying process, they become part of his everyday life as “life goes on.”

Image credit: Jack Doherty

Together, these gallery stops offer moments to pause, linger, and connect with the area’s artistic spirit.

From gallery-hopping to discovering the intimate connections artists share with the coast, Cornwall’s #SecretSeason is a great time to explore Penwith’s artworld. Find a coastal retreat and be part of the artistic spirit…

When we think of mussels, it’s easy to drift to visions of sun-dappled terraces and bowls of moules marinière paired with a crisp white wine. But this belies their true nature: a winter coastal treasure…

These jewels of the sea are at their British best in the colder months (as are most shellfish in fact), when the waters are chilly, and these humble bivalves are plump, sweet, and full of flavour.

For centuries, Cornish mussels were a widely eaten and gathered seafood, harvested from rocky shorelines at low tide and simmered simply over fires, their briny flesh providing essential sustenance during harsh winters. Over time, French culinary traditions filtered into the UK and mussels found their way into more refined dishes, like the iconic moules marinière.

Today, Cornish mussels are celebrated for both their exceptional flavour and their role in sustainable seafood practices.

Mussels are farmed along the Cornish coast. Some are grown on the seabed, where they are dredged, hand-raked or harvested using water jets. Others are rope-grown, using toggled ropes fixed to anchors on the seabed and buoys on the surface in sheltered tidal waters.

“Farming shellfish has to be one of the most environmentally friendly forms of food production currently in commercial operation,” says Matt Marshall, from Porthilly Shellfish in Rock. “Our mussels are grown on the estuary beds of the River Camel in North Cornwall, which is the traditional way of farming them, but both rope- and seabed-grown mussels provide a high protein and nutrient-rich food.”

At Porthilly, the mussel farming process involves laying tonnes of baby mussel seed along selected areas of the Camel River bed and allowing them to grow to maturity.

“These areas have to be sheltered from any heavy storm action and have just the right surface – too stoney and the mussels can’t clump together, too sandy and the mussels will get buried,” explains Matt.

As a natural filter feeder, cleansing the water they live in, mussels are a boon for marine ecosystems and a low carbon foodstuff.

“Our mussel beds help support a thriving ecosystem, alive with wildlife including wading birds and a variety of fish and crustaceans,” says Matt.

The farmed mussels at Porthilly are harvested by boat and fully cleaned for sale at the farm, before making their way to fishmonger counters and coastal restaurant kitchens.

Image credit: Kota

“What I love about mussels is how much flavour they impart with very little cooking,” says chef Jude Kereama, owner of Kota and Kota Kai in Porthleven.

While most of us are familiar with the classic French moules marinière – shallots, garlic, white wine, double cream and parsley – they pair well with an abundance of different ingredients.

“At Kota Kai, we serve them three different ways – in a Thai coconut broth, in a marinière, and then in a Spanish style with chorizo, orange, chipotle chilli and some coriander. They soak up any flavour you put them with,” says Jude.

Image credit: Sam Breeze

“Another delicious dish is to do them puttanesca-style, with tomatoes, olives, anchovies and basil. I’d serve that with a crusty chunk of sourdough smeared in olive oil and a rub of garlic or over spaghetti.”

While cooking a steaming pot of mussels in a tasty broth is a failsafe option, Jude also likes to experiment with them in more unexpected dishes: “We turn them into fritters by making a simple batter with egg, milk and flour and then add chopped spring onion, coriander and maybe some sweetcorn.

“Lightly steam the mussels until they just open, let them cool off and then roughly chop them and put them into the batter. Fry the batter lightly, pancake-style over a medium heat until golden on both sides. At Kota Kai, we’d pair them with a nice seaweed tartare sauce.”

Image credit: Kota

Cornish mussels are available to buy at fishmongers across the county. Ask the fishmonger to debeard them for you as this can be slightly awkward to do at home with a knife. Matt recommends half a kilo per person as a starter or three-quarters of a kilo per person for a main meal – and possibly a few more for real shellfish enthusiasts.

When preparing, it’s important to make sure they’re clean, free of grit and still alive. Rinse them in running water over a colander and tap any open ones on the side of a bowl. If they’re alive, they should close up. If not, discard them. “Some mussels can be a bit lazy, particularly in the colder months, so give them a few seconds to close,” adds Jude.

Image credit: Kota

When cooking, it can be tempting to dial up the heat and leave them to it, but this can risk overcooking, leaving the texture rubbery. “Whichever sauce you cook them in, they are best when they just open,” says Jude. “Any that don’t open, throw away. It’s as simple as that.”

Whether enjoyed by a roaring fire or as the centrepiece of a family gathering, Cornish mussels are a testament to the simple joys of the sea – best savoured when the waters are at their coldest and you’re nestled somewhere warm.

Sample freshly harvested shellfish served-up on the coast – or cook-up sea-friendly seafood – when you stay by the beach this #SecretSeason