Secret Season: Porth

West of Port Isaac, the cliffs and coves reveal echoes of the vanished people who once called this stretch of the Cornish coast home

Framed by the twin headlands of Doyden Point and Kellan Head, the narrow channel of Port Quin is a quiet place these days: a cluster of National Trust cottages, a stout harbour wall, a stone slipway. But two centuries ago, it would have been a hive of activity.

Imagine, the smell of fish and tobacco smoke, a boat hauled up on the slip. Up the lane, men are scooping salt into cellars to preserve the morning catch. Others work on seine nets, patching the mesh in the sun. There’s banter, laughter, salty cursing. On the cliff, a huer, or watchman, scans the horizon, looking for the shadow of the next shoal. When he sees it, he shouts ‘Hevva!’ and the men drop their tasks, clamber into boats and head out to sea. They’ll stay out as long as their nets can hold fish.

Sometimes it’s easy to forget places like Port Quin had a past beyond the postcards. Port Isaac local John Watts Trevan makes some fascinating fishing observation in his 1834 memoir. But apart from the old cottages and pilchard drying sheds (colloquially known as ‘palaces’), little remains of the industry now. What happened?

According to legend, Port Quin’s fishermen were all drowned by a terrible storm – perhaps as punishment for fishing on the Sabbath – and the village was abandoned. In fact, Port Quin was a casualty of economic decline. In the mid 19th century, dwindling fish stocks – particularly in the key species of pilchard and herring – and the slow collapse of Cornish mining forced thousands of families to emigrate – mostly to South America, Australia and Canada. The people of Port Quin were probably among them.

While the industry is gone, the coast path from Port Quin looks much the same as when the pilchard fishermen and the miners still worked here. Two shafts at Gilson’s Cove Mine, on the coast path from Doyden Point, can still be seen, marked by rings of slate stones. Lead, tin, silver, zinc and antimony – a whitish metal used to make pewter, paint and make-up – were the principal ores mined here. In the cliffs around Port Quin, mineral streaks the rock like veins.

Near Gilson’s Cove Mine stands another oddity: Doyden Castle, a mock-Gothic folly, built around 1830 by a Wadebridge merchant called Samuel Simmons, who’s said to have used it as a private pleasure den for partying, drinking and gambling.

From Doyden, the coast path climbs up and over Trevan Point – a natural watchtower at 213ft above sea-level, serving-up a fine panorama stretching west to the craggy headland of The Rumps and the offshore island of The Mouls.

From Trevan Point, the path descends to Epphaven Cove, a rugged little inlet that’s good for rock-pooling, which also has a small waterfall and natural plunge pool for cooling off on a hot day. The slate here has sometimes yielded fossils, too, so keep your eyes peeled.

Around the headland to the west lies Lundy Bay, another rocky beach where you can climb down via wooden steps. The cliffs and fields around here are managed by the National Trust for wildlife, cutting back the hawthorn hedges and preserving grassland habitat; it’s a good place for spotting wildflowers, butterflies and birds of prey.

Just above the western edge of the beach is Lundy Hole, where you can peer down and watch the breakers booming under the rock arch: this sea cave is said to have been the hiding place for St Minver fleeing the devil.

A little further west is a cleft in the cliff known as Markham’s Quay. Here, sand and gravel were hauled up from the beach by horse-drawn carts. It’s also a fabled smugglers’ haunt, where contraband was landed under cover of darkness. Was Markham a smuggler, or one of the Preventive men who patrolled the coast and tried to catch them? No one remembers now.

From here, you can choose either to turn back to Port Quin or hike out another couple of miles past Carnwether Point to The Rumps, which snakes seawards like a sleeping dragon. During the Iron Age, one of north Cornwall’s most important promontory forts stood here. You can make out the outline of the ditches and embankments that protected the fort from assault. Archaeological excavations have turned up artefacts suggesting the people here traded with the Mediterranean.

Nowadays, the headland is a cracking spot for a picnic. In summer, the rocky island off the point, The Mouls, hosts squawking colonies of gannets, kittiwakes, fulmars and sometimes puffins (lundy derives from the old Norse word for puffin). It’s also an infamous shipwreck spot: in 1995, when the Maria Assumpta, the world’s largest square-rigged sailing ship, went down while trying to make Padstow harbour, with the loss of three crew.

All told, the walk from Port Quin to the Rumps is a 6.5 mile return journey – a three-hour hike, there and back. To ease tired limbs, you can book a shipping container sauna courtesy of Cornish Coast Adventures, overlooking the beach where the fishermen once worked. Times have certainly changed at Port Quin.

Discover stays along Cornwall’s storied north coast this Secret Season.

Discover the ultimate cliffside sanctuary with bespoke interior design, a heated pool and cedar hot tub, seconds from the wind-whipped shoreline of Mawgan Porth. The Beach House is part of The Iconic Set – a collection of our most remarkable retreats – and it’s easy to see why…

The Beach House gives you the best of both worlds. Dive into north Cornwall’s vibrant saltwater lifestyle just footsteps from your door and spend the day amongst the swell. Head back home to the secluded luxury of your clifftop haven and unwind.

The Beach House gives you the best of both worlds. Dive into north Cornwall’s vibrant saltwater lifestyle just footsteps from your door and spend the day amongst the swell. Head back home to the secluded luxury of your clifftop haven and unwind.

Here’s how you could spend seven days at this laid-back retreat, from coast path exploring to poolside lounging.

Check into The Beach House and get acquainted with your new home for the week. Admire the sea views, pick which interior designed room you want as your own, and maybe test out the water in the clifftop heated pool. Unpack your Cornish Food Box goods which were waiting on arrival and fire up the barbecue. If you don’t feel like cooking, stroll down to Mawgan Porth for an easy dinner at The Merrymoor Inn.

Just five minutes from your door, Mawgan Porth beach awaits. Spend the morning soaking up the sun, building sandcastles, or splashing in the surf. Little ones can paddle in the shallow stream, while thrill-seekers can hire a board and get in the waves. Refuel at Catch Seafood Bar & Grill, where fresh fish is served with a view.

Spend the day making the most of The Beach House’s spa like amenities. Swim lengths of the pool, sink into the cedar hot tub, or lounge poolside with a good book. Take advantage of the cocktail station and serve up martinis or pina coladas with a view. Watch the sun set and stargaze or head inside for a cosy film night by the fire.

Pack a hot flask and head out on a scenic walk along the South West Coast Path to Watergate Bay. This moderate route takes you along dramatic cliffs and offers stunning views of the Atlantic. Once you’ve arrived at the bay, treat yourself to lunch at The Beach Hut, a laid-back post-sea restaurant right on the sand.

Head in the opposite direction on the coast path to Bedruthan Steps, a dramatic viewpoint where you can admire the awe-inspiring rock formations and explore the rugged coastline.

Stop by the Carnewas Tea Rooms for a traditional Cornish cream tea (jam first, of course!).

If you time it right you can catch the sunset sink into the horizon before heading back for dinner at your retreat.

Drive 20 minutes to Padstow, a charming fishing village that’s a haven for foodies and shoppers. Explore the boutique shops and art galleries, then take a wander along the harbour.

Enjoy a Michelin-starred experience at Rick Stein’s Seafood Restaurant or opt for fish and chips by the harbour. In the afternoon, hire bikes and cycle the Camel Trail, a family friendly bike trail that winds along the estuary.

Enjoy one final morning swim, surf or beach walk down at Mawgan Porth. Grab a takeaway lunch from The Beach Box to maximise time on the sand. Soak up the Cornish air, pack up and plan next year’s trip to The Beach House.

Stay at The Beach House, Mawgan Porth and indulge in Malibu-style poolside living on the Cornish coast…

Browse all Mawgan Porth retreats.

Colder, but not unwelcoming, what is it about the atmosphere of the coast in winter that draws us in? And why is maintaining our connection to nature year-round so important?

Summer is the peak of coastal activity: as temperatures drop, t-shirts are swapped out for woolly jumpers and the shore empties out. The sea turns an icier shade of blue, and as nature winds down around us, we often follow suit. But what do we miss if we miss out on time by the sea? And what draws us to the coastline in the colder months?

Image credit: Abbi Hughes

There’s beauty to be found in the cold, especially along rugged stretches of coast. A change in the seasons doesn’t have to keep us away. In fact, this darker, cooler atmosphere can be what draws us in.

Writer Wyl Menmuir’s book Draw of the Sea examined people’s relationship to the coast. For Wyl, winter is a time to appreciate the shifts in the landscape – nature is exposed and heightened. And by the sea, we’re at a boundary line: “Perhaps we can see nature at its rawest when we’re standing on the edge of the land, rather than in the middle of it. It taps into our desire to experience the sublime, which is something I’ve always been interested in.”

The sea might be turning colder, but the waves get bigger, and its colour becomes deeper, more complex. Weather patterns shift, affecting the way water moves, and all of this becomes so much more noticeable.

The sea during winter can put things in perspective, says Wyl. This comes with being at odds with nature at its most volatile – and that’s exciting, whether you’re right there in it, or watching from afar. “I can sit on the cliffs and watch surfers riding enormous waves in the autumn and winter swells, here in Cornwall on the north coast,” he explains. “And it’s those times where I see people riding really challenging waves, and, for me, the sea is just more interesting to watch when there’s a lot more movement in it.”

Against the high winds, dramatic cliffs and outcrops, this is where comfort is found. Wyl finds that the long views of the coast, the water, give a sense of perspective. Against the backdrop of something as expansive as the sea, our problems and fears feel smaller, more manageable.

Wyl compares that feeling, of standing on the cliff face, looking out at the water, to staring up at a dark sky full of stars. After confronting the enormity of nature, we feel more comfortable in our place within it. There’s a certain meditation to be found.

Image credit: Abbi Hughes

The wind, the skies, the sea, all have a profound effect on the mind and body. The human connection to nature is a powerful one – for many, it’s the key to surviving through tough times, a way to keep centred. Lizzi Larbalestier, of Going Coastal Blue – a blue health coach, spends time in blue spaces all year round, and encourages others to do so too, whether it’s actually getting into the water, or simply walking alongside it.

Movement, Lizzi says, is crucial for mental and physical health. “The coast encourages us to get outdoors, dressing for the weather to enable us to take in the fresh air and embrace the elements, creating a primal sense of nature connectedness that promotes stress reduction and improves sleep.”

As the coastline quietens down during winter, transforming into a more peaceful and quieter environment – it is a great place to pause and reflect on the year, with plenty of space to absorb the sweeping horizons, vast open skies, and glistening shoreline. “Spending time in blue space,” Lizzi says, “allows us to breathe well, to slow down, to think more clearly, to feel much more connected with ourselves, with each other and with the planet.”

With the approach of winter comes a desire to hunker down, sink into creature comforts, embracing warmth and light wherever we can find it. As Lizzi notes, getting natural daylight and spending time outdoors during this time of year is incredibly important for our wellbeing and that includes our physical and emotional health. But sunlight can be scarce mid-winter, so we should embrace and enjoy it where we can.

Spending time by water is great for our mental health. Water, in all seasons, in all forms, is inherently soothing. We are drawn to its feel, its colour and sounds. Lizzi explains that simply watching the waves can calm us down, creating “attention restoration with less complex and frenetic landscapes allowing our mind to drift into a more meditative state.”

“We breathe differently at the coast,” explains Lizzi, “positively impacting our heart rhythm, lowering blood pressure and enabling our nervous system to move into a parasympathetic state of rest and recovery.”

Image credit: Abbi Hughes

Lizzi depicts the sea as a “therapist or health practitioner, a partner for our lives to guide our intuition and keep us well”. “We gain a lot from a strong connection to the coast, but our relationship with all of nature is symbiotic.” she says. We can gain from it, but also need to give back.

“Take three for the sea,” recommends Lizzi. “Conduct a mini beach clean or get involved in a large community beach clean with the local community – these organised collective events not only help the ocean but being part of something purposeful in the form of community activism and advocacy can boost positive ‘feel good’ neuro chemicals like oxytocin and dopamine associated with what is known as the ‘helpers high’.”

From experiencing the sublime to feelings of perspective and breathing in the physical and mental benefits of being by the sea, there’s much to draw us to that unique beach atmosphere in the colder, quieter months.

This #SecretSeason, stay footsteps from the coastline: experience the beach atmosphere benefits.

Hushed beaches, misty cliffs, and the gentle sounds of the tide, this is Cornwall’s #SecretSeason – a moment for reflection, meditation, and creativity – a perfect time to visit Penwith’s artworld.

Penwith – Cornwall’s westernmost tip connected to the wild Atlantic, stretching all the way from Hayle around to St. Michael’s Mount – has long been celebrated for its rich artistic heritage. Its raw and rugged beauty is inspiration for both artists and art lovers. And from Marazion to St Ives, local artists and galleries recreate the winter landscape in softly coloured paintings and ceramics.

Cornwall’s #SecretSeason is a perfect time to discover its thriving art scene, so we visited some of this season’s exhibitions and hear from two local artists, Sarah Woods and Jack Doherty, on how winter shapes their creative processes and deepens their connection to the coastal landscape.

Begin your journey at Penzance, Cornwall’s major port town. In its quiet historic streets, you’ll find Penlee House Gallery & Museum home to an impressive collection of Newlyn School paintings. Upcoming in February 2025, The Shape of Things: Our place in a changing climate, will feature works of local artists who explore how Cornwall’s shifting land- and seascapes respond to environmental changes, inspiring hope and action for the future.

Image credit: Sarah Woods

Newlyn-based painter, Sarah Woods, paints her personal interpretation of the shifting atmosphere from her cozy studio. “Winter along the west coast has a timelessness – a feeling of the land and sea in harmony.”

With changing seasons, she witnesses the landscape quietly breathing and shifting as well. This way, her collections are unique to each season – her newest series captures this shifting landscape in autumn, drawing inspiration from “a palette rich in deep earthy tones, gathered from elemental movement of the ocean and a coastline warmed with autumnal light.”

As winter takes hold, the colours she mixes evolve again inspired by low-traveling light and dark ocean hues. The light “has a clarity that comes with the cold,” she says, slowing down the pace of things while the “landscape breathes.”

Image credit: Sarah Woods

In her studio, Sarah focuses on the process of painting rather than the outcome, describing it as “a continuous flow of time balanced between the coast at the studio.” Her practice is intuitive and tactile, shaped by an immediate response to the forms and colours she observes in the landscape. Whether focusing on large-scale canvases or intimate studies, she creates pieces that reflect nature’s rhythm, translating Cornwall’s wintery calmness into meditative works of art.

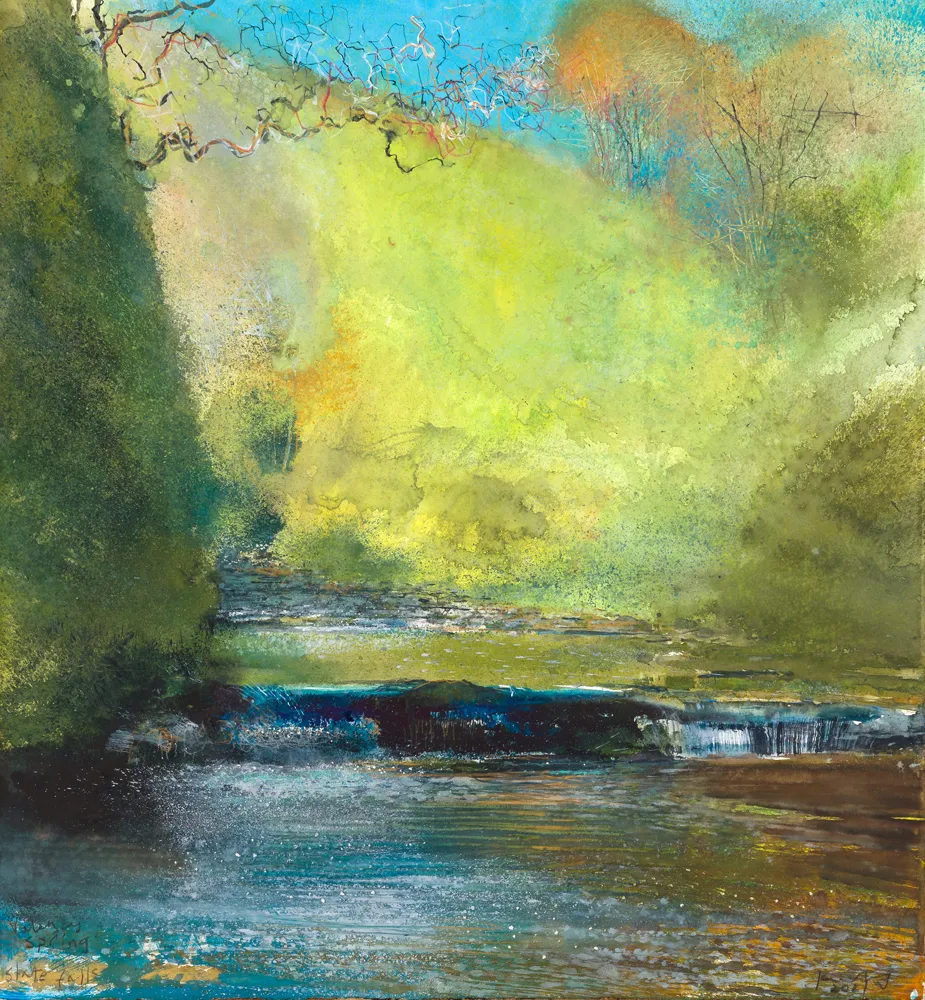

Building on Sarah’s introspective approach, the next stop on this artistic journey takes you to the small town of St Just. Here, The Jackson Foundation invites you into its industrial space where art and nature become one. The current exhibition showcases Kurt Jackson’s paintings, taking inspiration from Valency Valley in north Cornwall.

Image credit: Jackson Foundation Gallery

It features large-scale works capturing the valley’s wooded banks, flowing waters, and the Boscastle Harbour. The collection reflects Jackson’s philosophy that “no man ever steps in the same river twice” – each piece is a silent reflection on both a nostalgic past and a scenic future.

Image credit: Kurt Jackson

This play between nature’s physical environment and artistic response also unfolds in Jack Doherty’s ceramic work. In 2008, he became the first lead potter at Leach Pottery in St Ives, after it was refurbished, carrying forward its “modernist awareness of material and technique.” Today, Jack’s work is shaped by Cornwall’s jagged environment and changing weather. His recent exhibition, Weathering, reflects Cornwall’s shifting weather patterns and the passage of time that shapes not only the landscapes but also his ceramics.

Image credit: Jack Doherty

“The powerful combinations of colour in the grey, wet wind-blasted stones and moorland of West Penwith” inspire Jack’s minimalist approach. Using just one clay, one colouring mineral – copper, sourced from Cornwall’s mining history – Jack’s soda-fired porcelain creates a striking palette of greys, russets, and flashes of cerulean, all without glazes.

“The winter weather is an ever present influence on how we live here,” he says. Even when the dampness and wind challenge Jack’s drying process, they become part of his everyday life as “life goes on.”

Image credit: Jack Doherty

Together, these gallery stops offer moments to pause, linger, and connect with the area’s artistic spirit.

From gallery-hopping to discovering the intimate connections artists share with the coast, Cornwall’s #SecretSeason is a great time to explore Penwith’s artworld. Find a coastal retreat and be part of the artistic spirit…